Celebrating Women’s History Month with some of Rhode Island’s #ArchivesAwesomeWomen

Celebrating Women’s History Month with some of Rhode Island’s #ArchivesAwesomeWomen

by Rebecca Hansen

In September of 1831, Elleanor Eldridge stopped for a night to rest at Angell’s tavern. She had been headed to visit friends in Massachusetts, but, overcome with a high fever, aches, and chills, her illness prevented her from continuing. The next morning, she felt no better and feared an attempt to leave. Her brother George asked the landlady if they could spend the day at the tavern, and she agreed. It was a request that would change the course of Eldridge’s life.

—

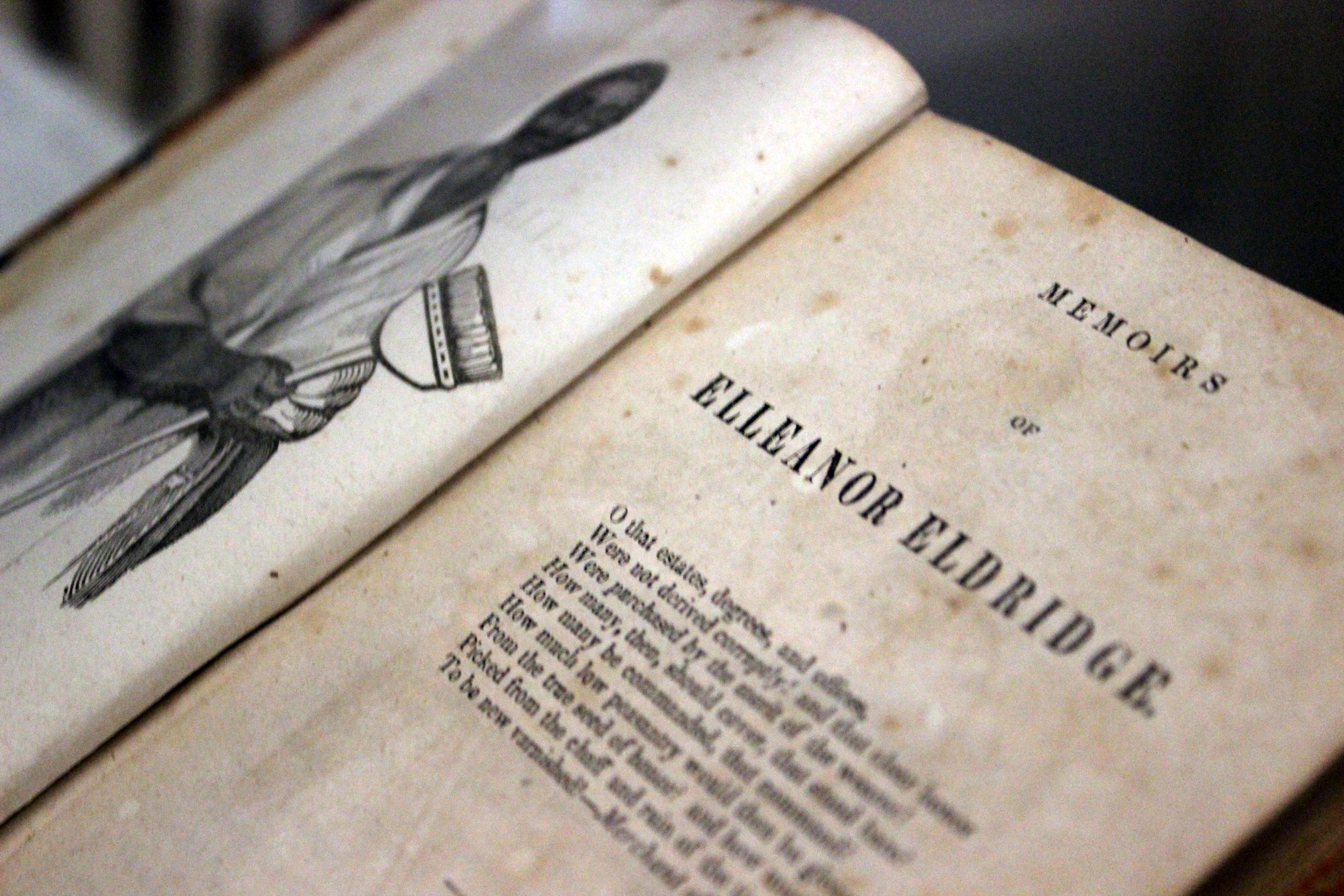

Eldridge, a woman of color, had made a name for herself as a successful entrepreneur, pulling herself up out of poverty. She was likely born on March 26, 1784, in Warwick, R.I. Her story is told in the Memoirs of Elleanor Eldridge (1838), by Frances Harriet Whipple Green, a first edition of which is in the Rhode Island Historical Society’s collections at the Mary Elizabeth Robinson Research Center.

According to her memoirs, Eldridge’s paternal grandparents had been tricked into boarding a slave ship in Africa. Her maternal grandmother was Mary Fuller, likely a member of the Narragansett tribe. When Fuller was looking to get married, she struggled to find a partner – her tribe had been decimated by colonial violence, and there were roughly two women to every man. Like many Narragansett women at the time, she turned to the slave trade to look for a husband. She bought Thomas Prophet, freed him, and they married.

Years later, Eldridge’s father, Robin Eldridge, won his own freedom fighting in the Revolutionary War. After her mother died, 10-year-old Eldridge worked as a dairy maid in the prominent houses of Rhode Island. By all accounts, she was an industrious worker, producing “four to five thousand weight of cheese annually,” according to a former employer cited in her memoir.

As she grew older, she continued to work, pushing aside everything she saw as a distraction. When Green, her biographer, asked Eldridge why she never married, she responded that it was a waste of time, that “while my young mistress was courting and marrying, I knit five pairs of stockings.” Eventually, Eldridge saved up enough to buy a plot of land, build a house, and rent it out. She supplemented her income with odd jobs, whitewashing, doing laundry, and wallpapering, and soon saved up enough to buy a second house. By 1827, she owned two house lots, a small house in Warwick, and a large house in Providence.

Her success brought her attention, and it wasn’t always positive. When she left town and took ill in Angell’s tavern, rumors spread. Two men from Providence overheard that she was sick, and reported the news to friends. The report snowballed, and soon many believed her to be dead.

Eldridge eventually made it to Massachusetts and stayed for a time to recover from her illness. When she returned to Providence, she went to the baker to buy bread for dinner, and a boy working at the bakery refused to sell it to her. “Don’t come any nearer! – don’t Ellen, if you be Ellen – cause – cause – I don’t like dead folks!” he’s quoted in Green’s account of the incident. It took some time to reassure him that Eldridge was, in fact, alive. Green writes, “Had the boy reflected a moment, he would have seen that it was out of all rule, and entirely without precedent, for a ghost to cry for bread; but Jamie, like many of his species was no philosopher.”

Eldridge soon discovered that her creditors, those she had borrowed from when building her house, believed she had died, as well. In an effort to regain the $240 she had borrowed, one of her creditors put a lien on her house. She promised to pay him back, continued to pay interest, and believed everything to be fine.

But, when she left town to visit a friend, the creditors descended once again. What unfolded was a confusing array of manipulations, culminating in the seizure and sale of her biggest house. The circumstances of the sale remain suspicious: The creditors could have easily sold her smaller house or one of her plots of land to pay off her debt. Instead, they seized the largest, never legally advertised it, and sold what was likely a $4,000 home for $1,500. It was a case of collusion, an abuse of power directed at a woman they believed couldn’t defend herself.

But they underestimated her. Eldridge contacted the State’s Attorney, and he told her to bring forward a case of Trespass and Ejectment against the man who had purchased her property. She also approached many of the women whom she had worked for, and they banded together to help. Much of what we know about Eldridge comes from this effort: Green wrote Memoirs of Elleanor Eldridge to raise money for the case. In its introduction, 13 of Eldridge’s former employers, all women, testify to her character. The book is a further testament to Eldridge’s work ethic, as well as to the injustice she faced from, as Green writes, “the wanton carelessness, if not the wilful and deliberate wickedness, of men.”

It reads, at times, like a romance novel. Green describes Eldridge’s early love life, noting, “Whether Elleanor, herself, ever yielded to the witching influence of the tender passion, remains in the Book of Mysteries to this day. Sometimes, with a low, quick breath – I could almost imagine it a sigh – she would say, “There was a young man – I had a cousin –He sent a great many letters – .”

But, the memoirs also speak to Green’s steadfast political beliefs. She writes of Eldridge, “No MAN ever would have been treated so; and if A WHITE WOMAN had been the subject of such wrongs, the whole town – nay, the whole country, would have been indignant: and the actors would have been held up to the contempt they deserve!” And, “Elleanor has traits of character, which, if she were a white woman, would be called NOBLE. And must color so modify character, that they are not still so?”

As Eldridge tried to gain back her own property, she continued to fight injustices against her community in the legal system, managing her brother’s defense after he was wrongfully accused of beating another man. Meanwhile, the memoir and its sequel, Elleanor’s Second Book, also written by Green, raised enough money to fund Eldridge’s own legal battle. The suit against her creditors wasn’t settled perfectly, but Eldridge managed to buy back her property after raising additional money from within the community. In the end, she turned back to her work, telling Green of the legal system that she had “no desire to enter its mazes again.”

Both Memoirs of Elleanor Eldridge and Elleanor’s Second Book are available for viewing at the Mary Elizabeth Robinson Research Center. The RRC is open Wednesday through Friday (and each second Saturday of the month) from 10am to 5pm. Materials are stored in the closed stacks and will need to be paged by library staff. Materials are retrieved at 10:30am, 11:30am, 2pm, 3pm, and 4pm (books only).