This, the second of the summer’s pirate-themed blog posts, centers on the brutal pirate, Charles Gibbs. A Rhode Island native, Gibbs started out on a life of crime early (he “became addicted to vices uncommon to youths of his age”) and then never let up. After an impressive career with the US Navy (or so claimed Gibbs; doubt has been cast on much of his story), Gibbs tried his hand at the grocery business in Boston. After failing at that occupation, he returned to the sea and soon found himself engaged in a mutiny, which led without much delay into a life of piracy. Eventually captured, Gibbs was hung in New York on 22 April 1831.*

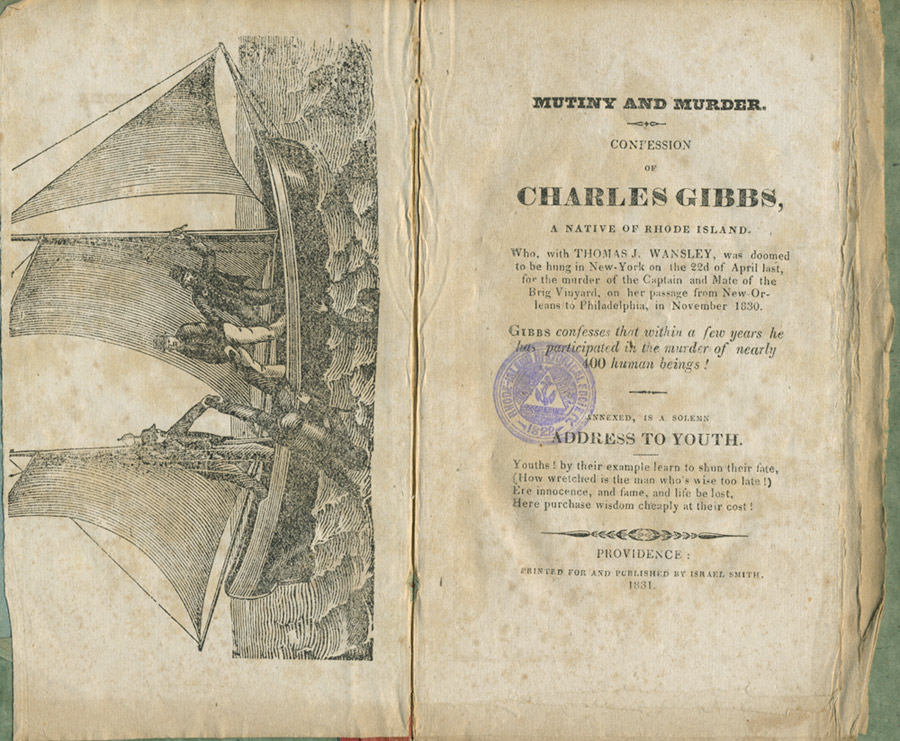

The story was a popular one from the outset: OCLC lists dozens of editions of Gibbs’ narrative published within a few years of the hanging, most following a similar pattern and reprinting practically identical texts. Many now survive in only a few copies; some are unique. The RIHS Library holds a number of these imprints, some of which will be discussed in the next post, but this post centers on Mutiny and Murder: Confession of Charles Gibbs, published by Israel Smith in 1831.** The first image below is of the book’s title page and frontispiece (disposing of a body overboard):

The lengthy subtitle offers a convenient overview of Gibbs’ story–which included an interlude of marriage and living “like a gentleman”–and rises to the crescendo of “the murder of nearly 400 human beings!”

The lengthy subtitle offers a convenient overview of Gibbs’ story–which included an interlude of marriage and living “like a gentleman”–and rises to the crescendo of “the murder of nearly 400 human beings!”

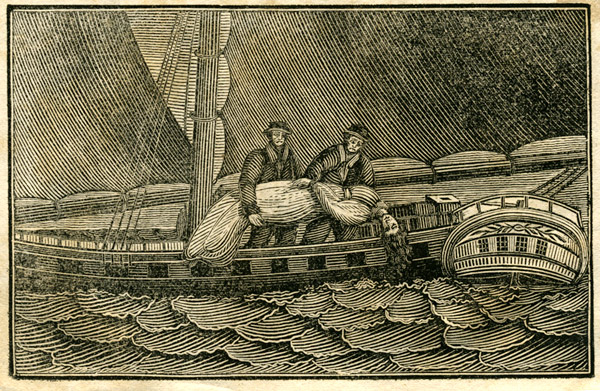

Below is a depiction of one of the more barbarous moments in a barbarous life: the pirates dropping a woman who had been treated brutally over the rail:

This image has a lot to recommend it: the stylized, scalloped waves set against the patterns of the sky and sails; the nautically- and perspectivally-challenged depiction of the ship; and the pathos of the (apparently foot-less) victim of the “horrid transaction”. But its greatest virtue might be the faces of the villains. First, a man who seems—if it’s not reading too much into a dozen or so lines cut into a woodblock to depict a face—hardened to the life of killing women and dropping them overboard:

His partner, on the other hand, doesn’t display the same sangfroid about the deed. (Gibbs himself claimed to have interceded on the woman’s behalf; perhaps the illustrator is attempting to capture that ambivalence.):

Mutiny and Murder, as is the case with many of the accounts, is clear to offer a moral to the story, which is made explicit in this case through an “Address to Youth,” which is dramatically placed between the account of Gibbs’ sentencing and his execution. (Another edition*** features an “Addenda, by a Lady,” which does the same job.) The book traces the seeds of Gibbs’ development to his youth (“he was refractory, ungovernable, and disobedient to his parents!”) and finds him penitent in his final moments. Considering his sins Gibbs says “I thought of my good and affectionate parents and of their Godlike advice” (p. 10). Though the narrative is made up mostly of violence and various other forms of anti-social behavior, it’s also scattered with notes of remorse, much in the manner of Hollywood gangster movies that end with the bad guys dead or in jail. Under the guise of “learning from their mistakes” we’re allowed to enjoy the violence and bad behavior.

In its moralizing and publication of confession, this account of Gibbs’ life and death hearkens back to the earlier tradition of the published accounts of the Ordinary of Newgate in England in the 17th and 18th centuries (available through the fantastic Proceedings of the Old Bailey website****).

The next post will take a look at some of the many other publications of the story of Gibbs’ life.

* Read the full narrative online at http://books.google.com/books?id=BJQqAAAAMAAJ (or stop by the library to view a real copy).

** Vault F 2161 .G44 M99 c.2

*** Last Dying Words and Confession . . . (Vault F 2161 .G44 L34, item 2)

**** The advanced search, which allows one to search by crime or by punishment provides hours of entertainment. Ever wanted to find the stories of people branded on the cheek for the crime of pocket picking? Now you can. (Martha Bromley seems to have been the only one so unfortunate in that particular manner.) And for more true crime stories, see the Harvard Law School’s Dying Speeches & Bloody Murder website, which makes digital copies of crime broadsides available.

This work is ….l Like.

From Argentina.

This website is awesomee! The more I study it the more I believe pirates can be interesting, but don’t wear well.