Karl Eschoff, an orphan boy taken in by Frederick the Great, leaves Prussia, becomes a merchant and woos a wealthy businessman’s beloved daughter.

Karl’s mother died when he was three years old and his grief-stricken father abandoned him. His maternal aunts raised him until he was 8 then sent him to live with a professor in Potsdam. Here he met Frederick the Great who took the boy as his ward, called him Karl Frederich Herreschoff and provided him a royal class education. Karl attended the Philantropinum School from 1779-1787. His name appears on a meritentafel (honor roll plaque) still on display at the school. His letter of acceptance can be read in “Newsletter to Friends and Relatives” March, 2013 by Nathanael Green Herreshoff III. After graduating in 1786 he set sail for America and changed his name to Charles Frederick Herreshoff.

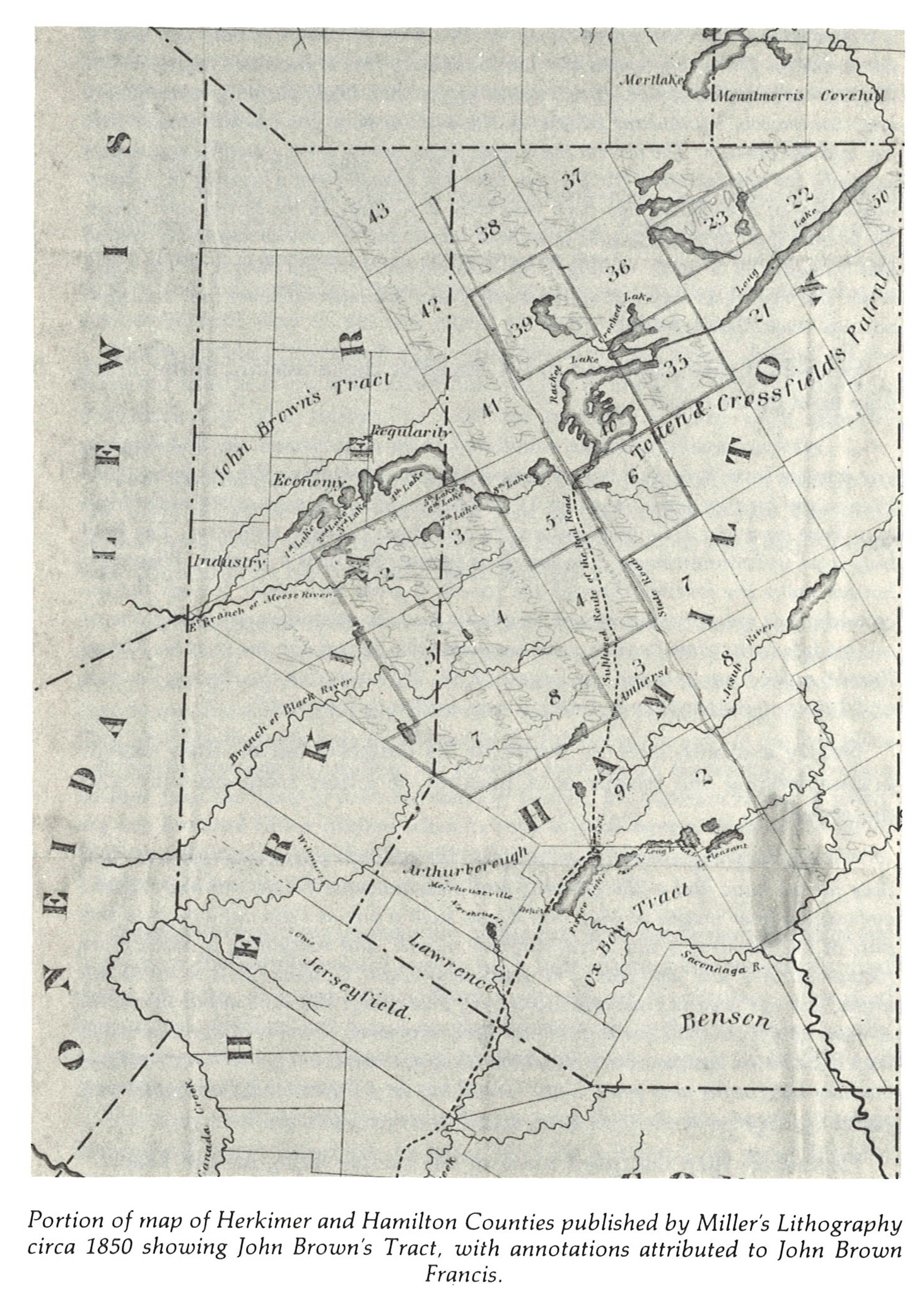

Not long after Charles arrived to start a new life, John Brown of Providence (1736-1803) was acquiring a tract of two hundred and ten thousand acres of land in Herkimer, New York. Brown erected several log dwellings, a sawmill and a grist mill, and set about making the land profitable.

Above map taken from John Brown’s Tract: Lost Adirondack Empire by Henry A.L. Brown & Richard J. Walton, we will come back to John Brown’s Tract shortly…

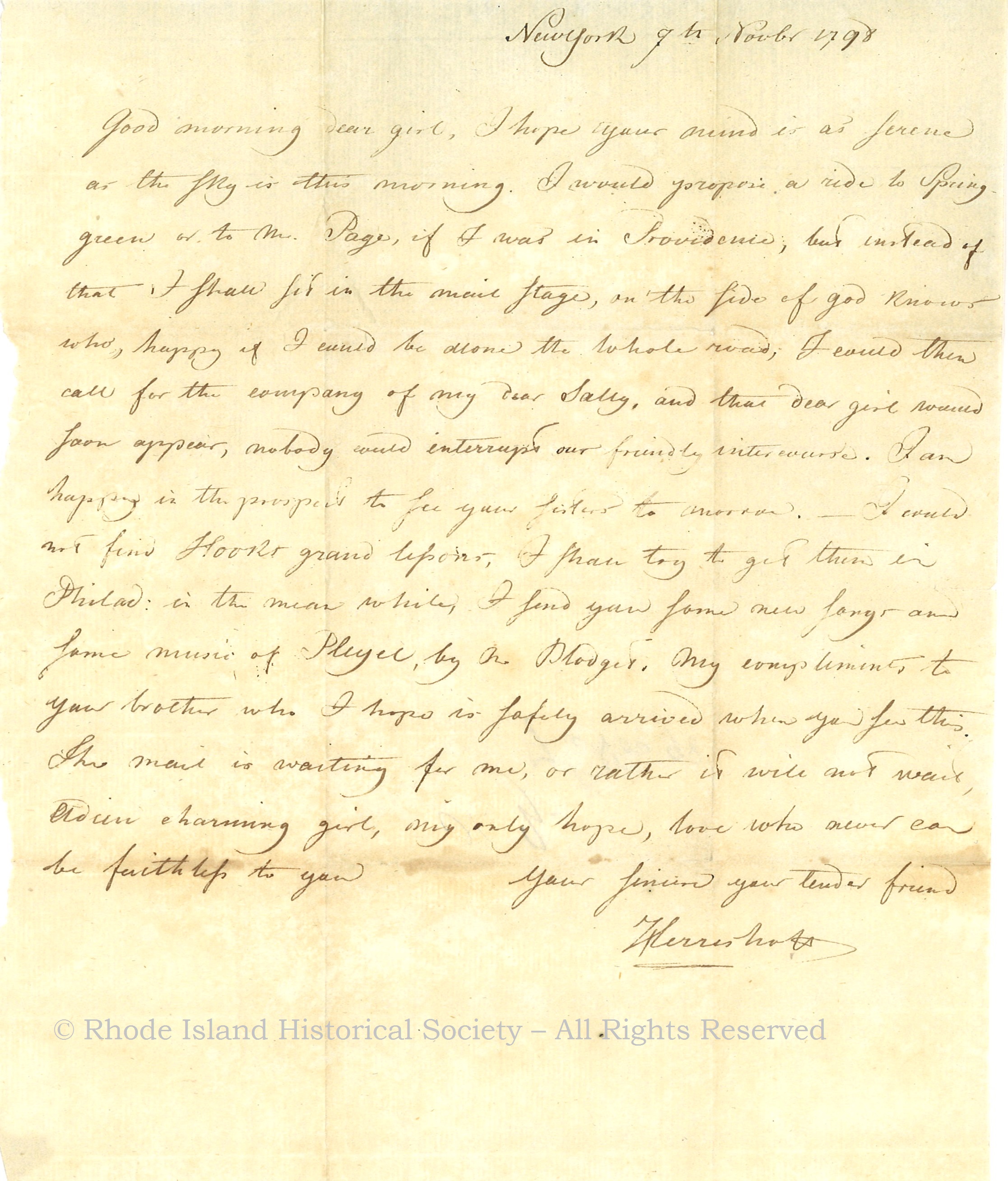

Around 1795, Charles was working in New York City for the mercantile firm of John Brown. Business brought him to Providence and introduced him to Sarah Brown, one of John’s daughters. Described as having a commanding appearance (over six feet tall with a well-formed physic), with a pleasant demeanor and charm to match, he must have made an impression. By 1798 he was writing his “Sally” love letters, full of longing, tinged with doubt and self-depreciating thoughts. The R.I.H.S. has in its collection many of the letters Charles wrote to Sarah.

Good morning dear girl, I hope your mind is as serene as the sky is this morning. I would propose a ride to Spring Green or to Mr. Pages, if I was in Providence, but instead of that, I shall sit in the mail stage, on the side of God knows who, happy if I could be alone the whole road, I could then call for the company of my dear Sally, and that dear girl would soon appear, nobody would interrupt our friendly intercourse. I am happy in the prospect to see your sisters tomorrow. I could not find Floors (sic) grand lessons, I shall try to get them in Philad: in the meanwhile, I send you some new songs and some music of Plaeye (sic) by Mr. Blodget. My compliments to your brother who I hope is safely arrived when you see this. The mail is waiting for me, or rather it will not wait. Adieu charming girl, my only hope, love who never can be faithless to you. Your sincere, your tender friend, Herreshoff.

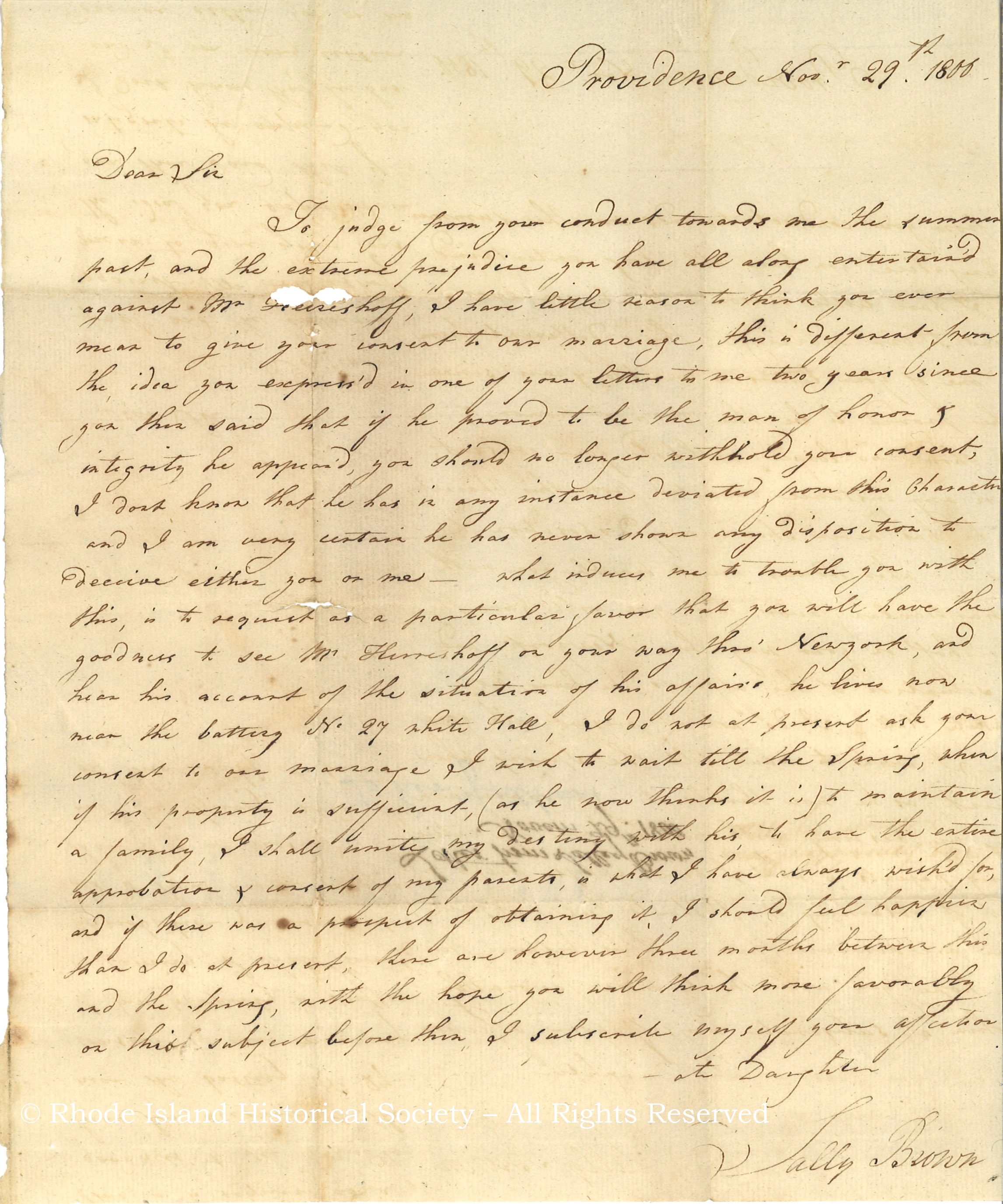

John Brown initially denied the young lovers’ request to marry, mostly due to Charles’ lack of name & fortune. Charles wrote to John expressing love for his daughter and plans for a successful future; Sally conversed with her uncle, Moses Brown (1738-1836), trying to win him over to their cause; and in November of 1800, she wrote a letter to her father, clearly frustrated with him.

Dear Sir, To judge from your conduct towards me the summer past and the extreme prejudice you have all along entertain’d against Mr. Herreshoff, I have little reason to think you ever mean to give your consent to our marriage…

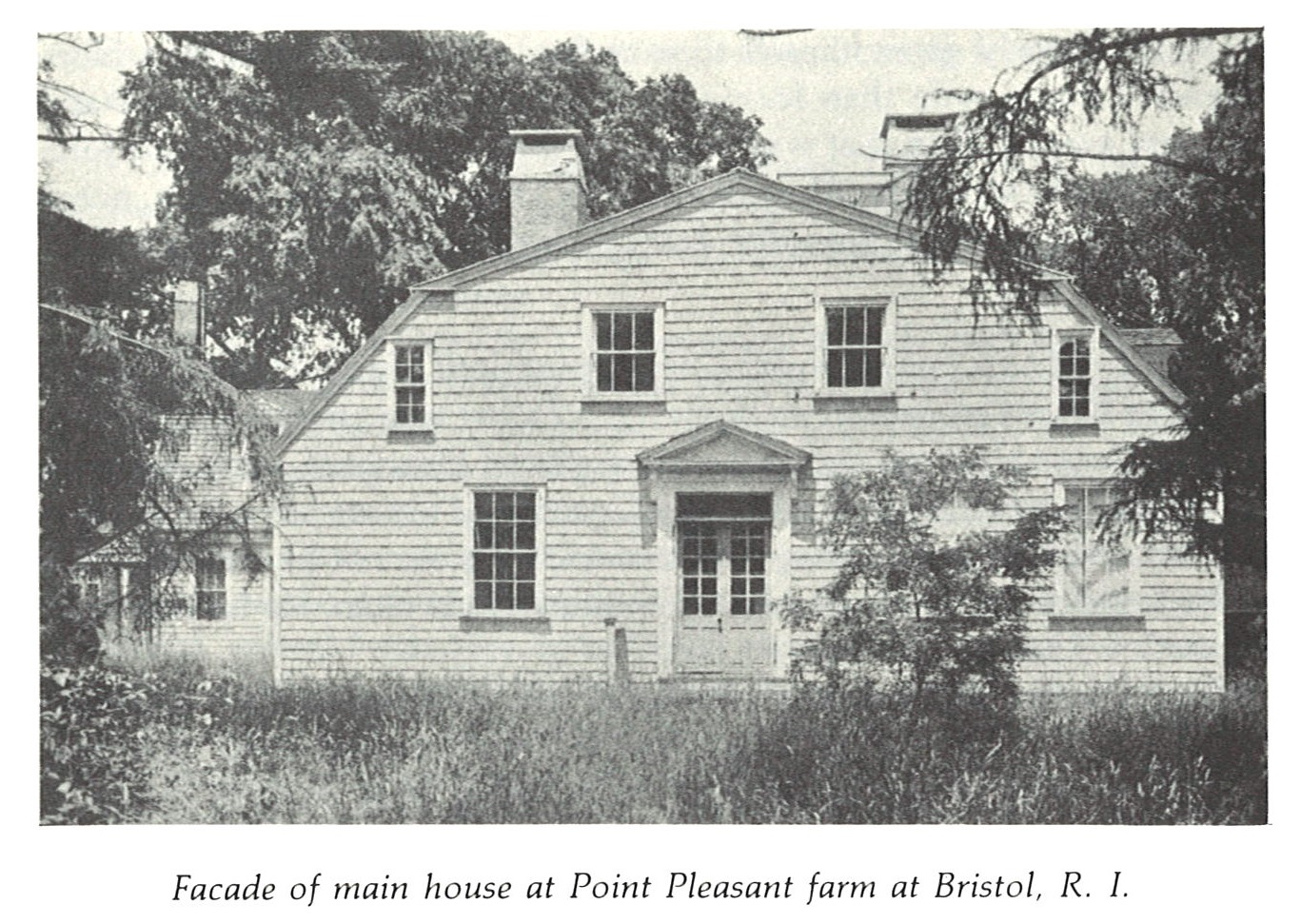

John Brown eventually gave in, whether due to the persistence of the couple, his fear of them running off or his own genuine like for Charles. They married on July 2, 1801 at John Brown’s house on Power Street and began married life on the Brown family’s Point Pleasant Farm in Bristol.

For the first ten years, things were happy and their five children, Anna, Sarah, John, Agnes and Charles Frederick, were born during this time. Then, in the fall of 1811, Charles and John Brown Francis (Sarah’s cousin) visited the isolated region that was John Brown’s Tract….

Upon arrival in the Adirondacks, it is said Charles declared that he “would settle the tract, or settle myself”. He spent most of his time at the Tract, away from Sarah and the children who stayed behind in Bristol. He repaired the buildings and mills John Brown had erected, cleared land, built a forge for the smelting of iron ore, and opened several roads to nearby settlements. He encouraged people to move onto his land with little success. The nearest town Boonville, was about 23 miles away. He went there often enough to get to know the townspeople and for them to get to know him, he was generally well-liked. While he had many ideas and spent lots of money, success alluded him. He tried raising sheep (they all died), farming (nothing would grow in the rocky soil), and mining (ore was scarce and not easily located). Years went by with Sarah writing and imploring him to come home but there was always another scheme to try or building to repair. One letter, written to his daughter Sarah in September of 1815, optimistically tells her “I have built a very snugg fair house, it is not quite finished, the masons are now building the chimney”. The house would become known as Herreshoff Manor and lived in by many other explorers of the region.

His letters became increasingly bleak and his mood darker as time went on. The separation was most hard on his oldest daughter Anna, who wrote him often. In the summer of 1819, she requested to join him at the Tract. His response to her was to stay home, that he was comforted thinking of his family together and that he would never want her in such an isolated and forsaken place. He closed this letter with hopes of seeing her soon. It was the last letter she, or anyone, ever received from him.

The most detailed account of Charles Frederick Herreshoff’s last moments is found in the historical narrative written by Megan Tracy:

“It was early on the morning of December 19, 1819, and Charles Herreshoff had not yet eaten breakfast. Autumn had come and gone, he still had not returned to Bristol, and his letters home had faltered and then stopped; now, the Adirondack Mountains, all the thousands of acres of John Brown’s Tract, were covered with snow. Herreshoff sat in his house in the wilderness, twenty-three miles from the nearest town, hundreds of miles from his wife and children, until, suddenly, the door flew open and Willard Johnson rushed in. Mr. Herreshoff, the young man sputtered. You should come right away – it’s the mineshaft – water’s burst through and it’s running like a mill race. Herreshoff had sent his employee on an errand to a recently sunk mineshaft, to check up on his latest attempt to find success in the rocky soil. And Johnson had returned with the news of a disastrous flooding in the mineshaft – the expense of pumping the water out would be crippling, it seemed, if it could even be done at all. When Herreshoff and Johnson arrived at the shaft, the only sound was that of the water continuing to gush; Herreshoff just stared. He continued to gaze at the rising waters for a minute, and then started back toward the house, with Willard Johnson trailing behind. By the time the two reached the house, Herreshoff was moving with such quick determination that Johnson could barely keep up. Puzzled, he watched as Herreshoff disappeared into the dark interior of the house and reemerged seconds later. Mr. Herreshoff – As the young man watched, Charles F. Herreshoff pulled out his pistol, placed it against his head – just below his right ear, aimed toward the sky – and pulled the trigger. The sound of the shot brought the Taft’s running from the house, but when their eyes fell upon the crumpled body of their employer, they froze. They could do nothing but stand in shock with young Willard Johnson; Herreshoff had died instantly.”

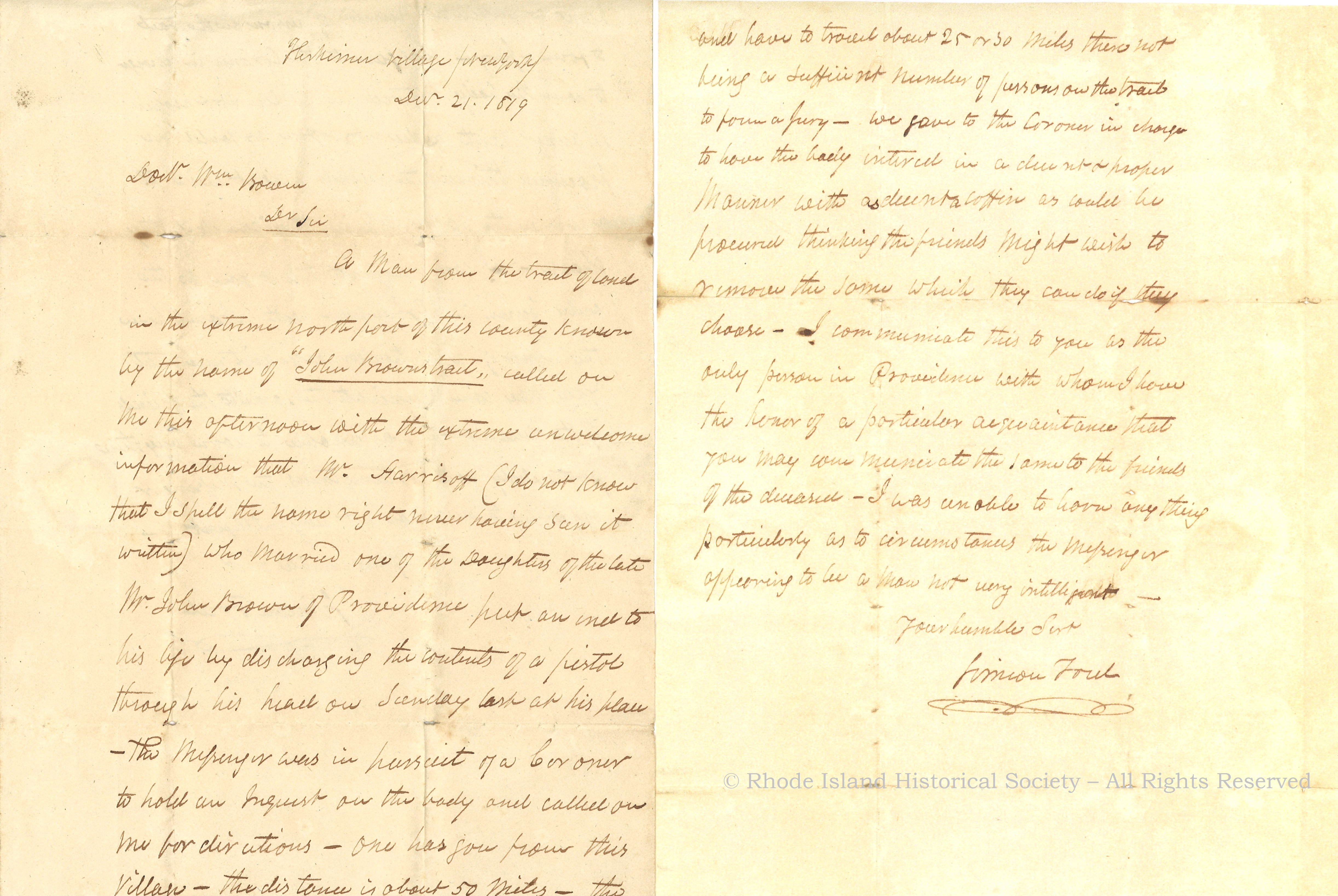

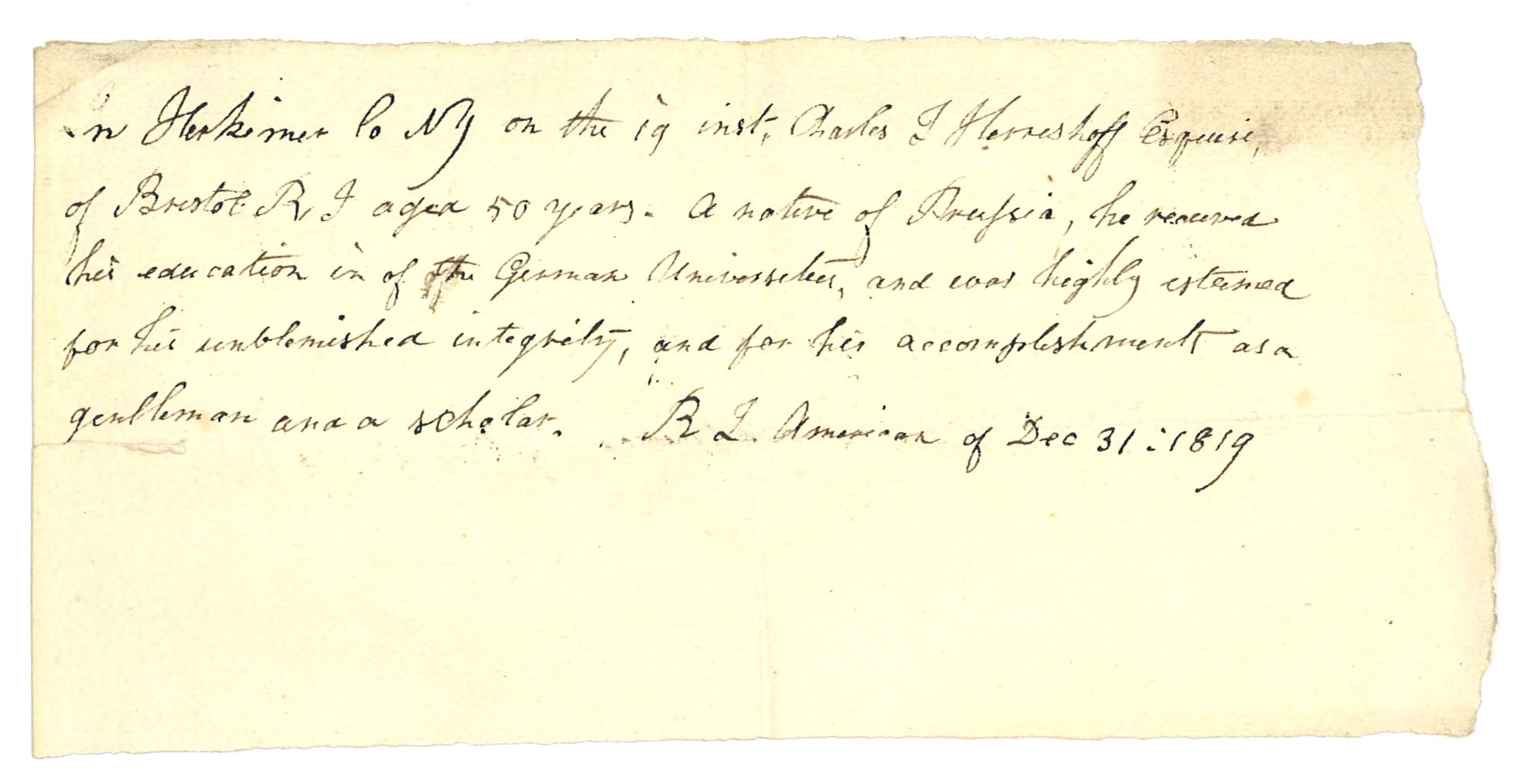

A letter, dated December 21, 1819 written by a man named Simeon Ford of Herkimer Village to “the only person in Providence with whom I have the honor of a particular acquaintance” Dr. William Bowen, informed the family of Charles’ death.

This concludes the fascinating story of a young man from Prussia who fell in love with a girl and toiled for years to be successful… but felt he failed. His name, however, is well known. His son, Charles Frederick Herreshoff III, went on with his children to become famous yacht builders and a google search of the name Herreshoff yields over 146,000 hits. Not a bad legacy for a “failure”.

~ Jennifer L. Galpern, Research Associate/Special Collections

REFERENCES:

Herreshoff-Lewis Papers, MSS 487

Brown, Henry A. L. and Richard J. Walton. John Brown’s Tract: Lost Adirondack Empire. Phoenix Publishing, Canaan, N.H. 1988 (F 127 .A2 B67)

Thorpe, T.B. “A Visit to John Brown’s Tract” Photocopy of article from Harper’s Magazine, no. 110, July, 1859. (F 127 .A2 T4)

Tracy, Megan. [Historical Narrative Concerning the Life and Death of Charles Frederick Herreshoff.] November 9, 1998. (CT 275 .H531 T7)

VF Biog H565c: Includes, “Newsletter to Friends and Family” by Nathanael Green Herreshoff III, March 2013 and Excerpts from Trappers of New York, or a Biography of Nicholas Stoner & Nathaniel Foster, by Jeptha R. Simms.

http://www.adirondackalmanack.com/2014/04/the-herreshoff-manor-witness-to-tragedy.html