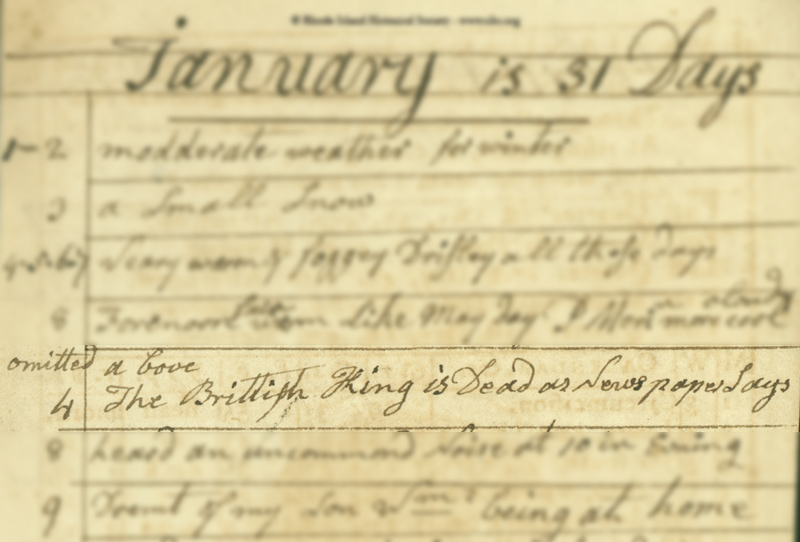

Our last post described Sanford Ross and some of the details of his daily life that are vividly brought out in the diary entries he maintained for fifteen years in his copies of the New England Almanack. One particular detail of the record for January of 1811 stands out:

January 4th: “The Brittish King is Dead our News paper Says”

The “British King” in question was none other than George III, and his death would have been a diary-worthy event indeed to someone who had been in his mid-twenties during the American Revolution.

It would have been even more noteworthy if it had been true: Although this entry is for 1811, George III wouldn’t actually die until 1820. The king certainly wasn’t in the best of health in 1811, but he was still alive.

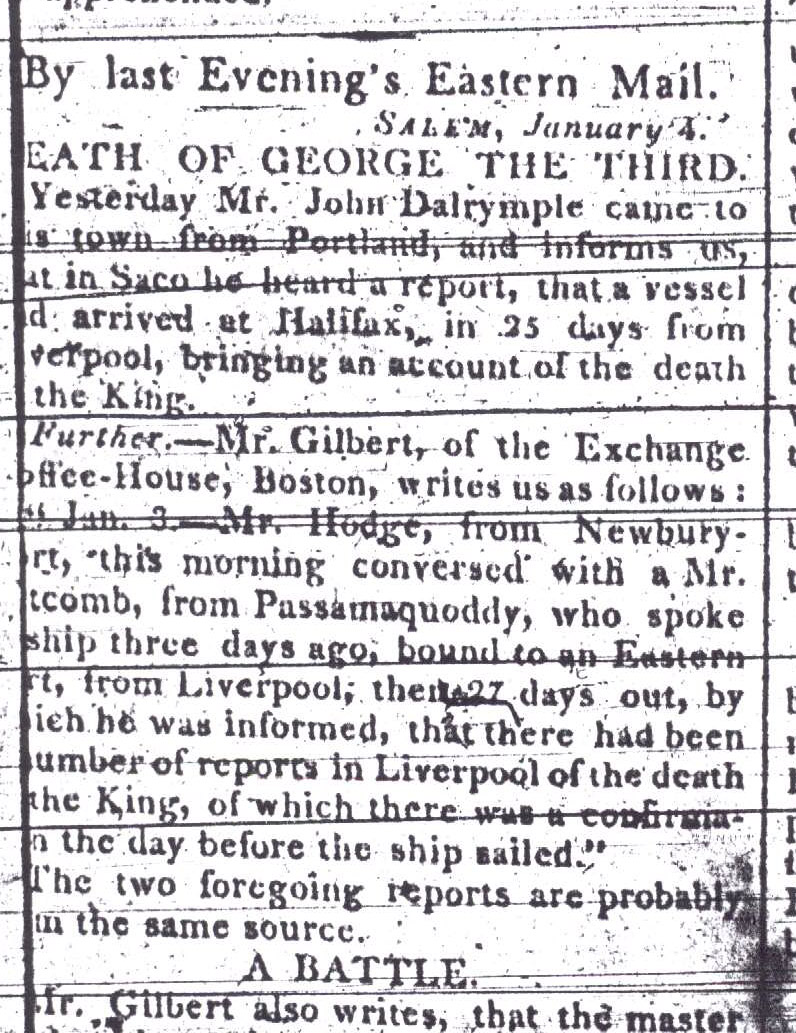

How did Sanford get it so wrong? Well, he certainly wasn’t alone in his belief, and this entry makes clear that he was only following the lead of his local newspaper. He might have read something like this, which appeared in the Providence Gazette of 5 January:

The account describes a Mr. John Dalrymple bearing the news into Salem and then below, although partially obscured by the poor image, a “Mr. [Ti]tcomb, from Passamaquoddy” who brought the news from Liverpool. The Newport Mercury‘s account varies in a few details:

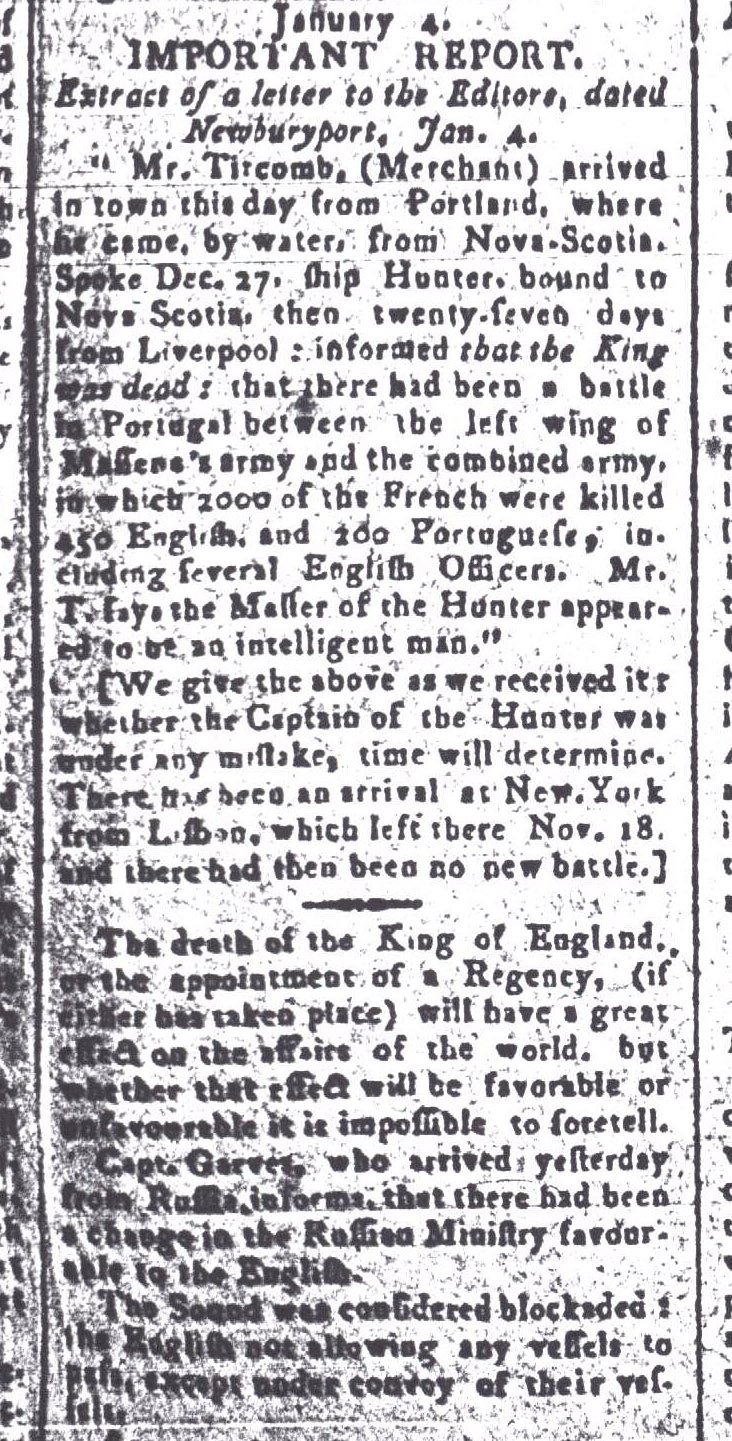

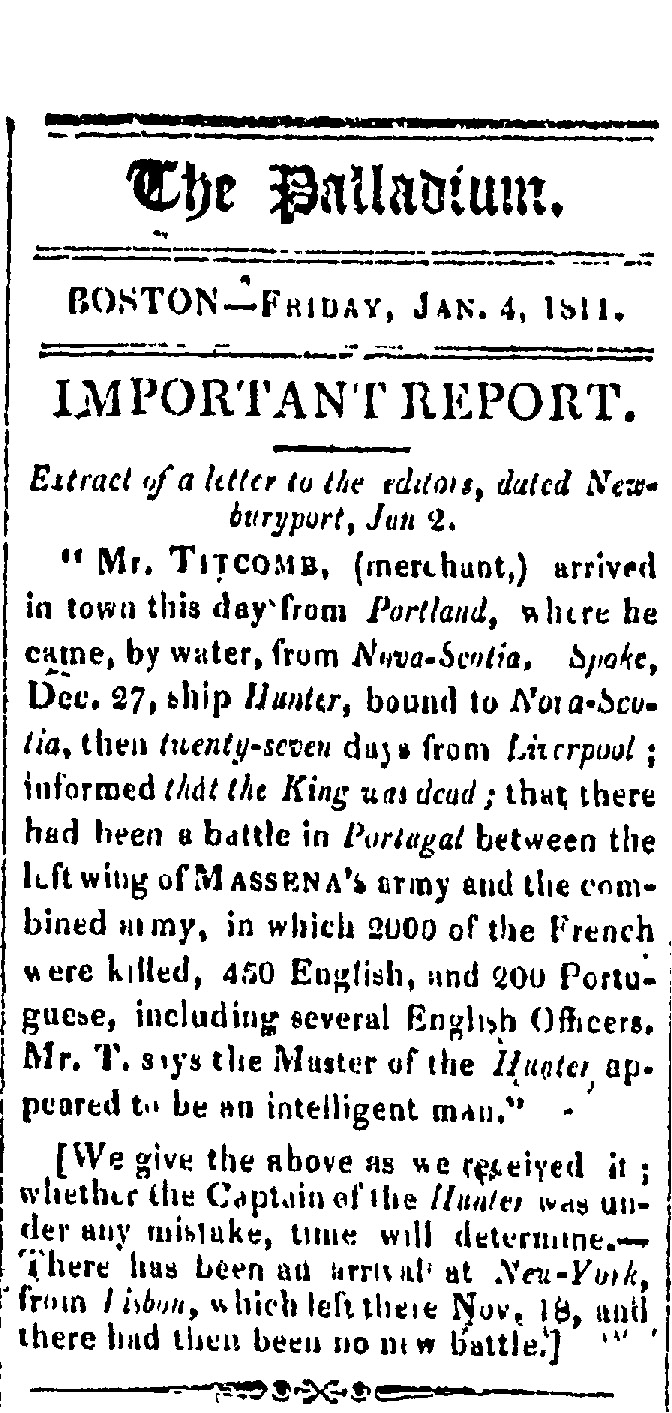

Passamaquoddy is nowhere to be found and neither is Mr. Dalrymple. A glance at the New England Palladium for January 4th offers an explanation:

For some reason the Providence Gazette has added (invented?) a Mr. Dalrymple and moved Mr. Titcomb from Portland to Passamaquoddy.

An already muddled account of the events is then set against the timeline of Ross’s response to them: the entries preceding and following this one are for the 8th of January, so that is presumably when he added it to his journal. But he added it as “omitted above” for the 4th, even though that is the date of neither the event (which had supposedly occurred a month prior) or the first appearance in the newspaper.

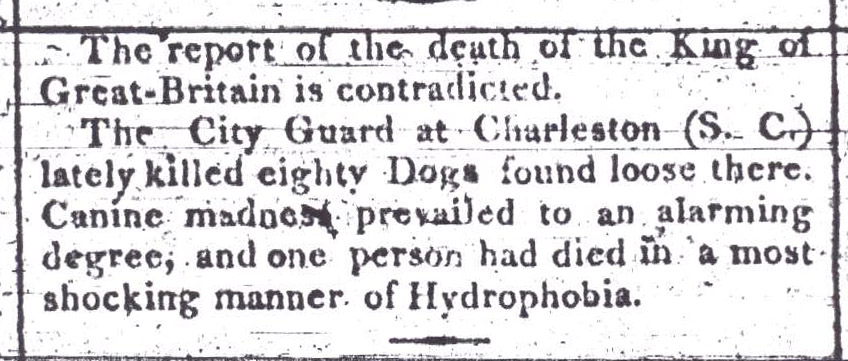

Eventually the misinformation was corrected, as here in the 12 January Providence Gazette, where the correction gets less space than “canine madness”:

The layers of confusion in this account of a non-event make it a perfect example of how our understanding a historical period or moment isn’t just about knowing what happened; it’s also about knowing what those contemporary witnesses believed was happening.

Hi, great comment. I look forward to your next post. Thanks, Jane