This year’s National Women’s History Month celebrates trailblazing women in labor and business. As the month winds down, here’s a look at some important contributions from women in Rhode Island’s organized labor movement during the 1920s and ’30s.

by Rebecca Hansen

“The foreman, especially those that worked the floor would … grant certain privileges … if the women were agreeable to uh a certain amount of uh what shall I say? Playing around,” said left-wing labor rights activist Ann Burlak, describing the conditions of women working in Rhode Island’s textile mills in the 1920s and 1930s. And sexual harassment wasn’t the only problem.

“Women who were having difficulties with their monthly periods … could stay out of work for the day that was most crucial … but they, the women who used to get very bad cramps during monthly illness, didn’t necessarily go to the doctor because it always cost money,” Burlak continues. But women were hesitant to bring up their concerns at union meetings, which were often dominated by men.

Burlak, known later as known as both “Seditious Ann” and the “Red Flame” for her communist views, as well as the “Hunger March Queen,” began advocating for women when she was just a teenager. When her father’s employment was cut down to a few days a week, 14-year-old Burlak took her first job as a weaver working for $9 a week in a Pennsylvania mill. But, when her boss offered a boy the same job for $12 a week, she knew that she had to make a change.

She told her father what had happened, and he said she should form a union. Burlak stayed quiet at her job, learning the skills needed to be a weaver, but eventually moved on to another mill, where she began her political work. She went on to lead protests, giving fiery speeches denouncing corporate greed and pushing for improved working conditions. By age 19, she was hired as an organizer for the National Textile Workers union.

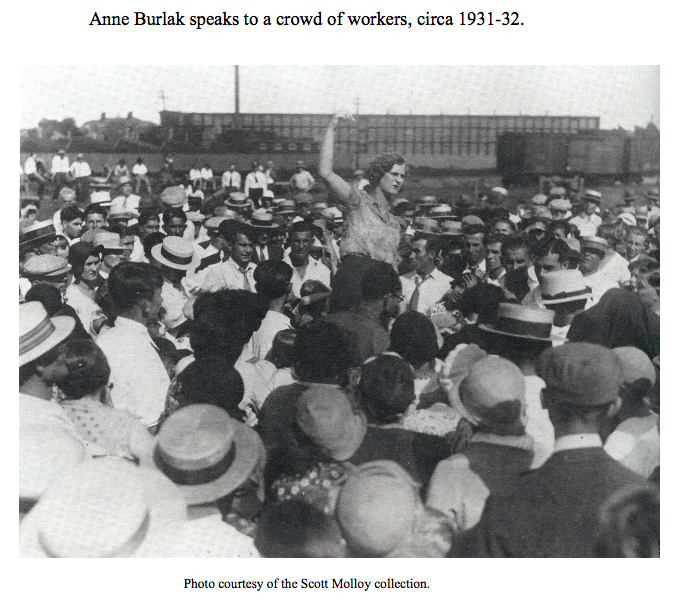

In 1931, Burlak was sent by the union to organize protests in Rhode Island. In the wake of the Great Depression, 40 percent of textile workers had their hours and wages cut back, and the resulting unemployment and unrest led to mass strikes throughout the textile industry. Unions, especially those with radical left-wing and Communist views, attracted an increasing number of members. But women often had difficulty accessing this community. Burlak led the charge in Central Falls and Pawtucket, calling for a restoration of wages, increased overtime pay, and the removal of efficiency experts who oversaw workers in the mills.

On June 16, 1931, the police accused Burlak of instigating violence by throwing pebbles at the forelady of a Central Falls mill. But the workers rallied around her. According to the Providence Evening Bulletin, the police had to call “every officer in the city” in order to arrest “girl striker Annie Burlock [sic],” who was supported by the entire picket line.

Burlak is just one of the many women who participated in the labor movement in the early 1900s. Many of their contributions are overlooked. Women were already at a disadvantage — the stated goal of many unions was a decent wage for male workers; a wage that would allow their wives to stay home. That goal, combined with the (misguided) notion that women would leave the workforce when they got married, meant that few unions would listen to women’s concerns.

Many historians have maintained that, as a result, there were few women involved in labor advocacy. Louise Lamphere argues that, although masses of women walked out of the mills in support of strikes following the Great Depression, there is little evidence of further participation. She notes that “perhaps … women had little to say about strike organization and were able to take few leadership roles even at the local level.” It was certainly true that women found difficulty reaching leadership roles, but to assert that they had “little to say” about the strike paints over the important contributions and unique perspective of many working women.

In 1926 in New Jersey, when a mill demanded that the wives of their male employees work night shifts, women organized a strike in protest. Newspapers reported that activist Elizabeth Kovacs led the picket line, all the while pushing her baby carriage through the crowd. Throughout the 1920s and ‘30s, activists like Burlak also organized soup kitchens for those on strike, seeking donations from fishermen and bakers who supported the cause.

And while many historians have argued that women avoided protests because of the violence of the period, recent scholarship suggests that women were actually more likely to participate in violence because they felt that police officers would treat them with more lenience. On September 12, 1934, the Providence Evening Bulletin reported that a female striker stood in the crowd of a protest, repeatedly demanding that soldiers shoot her. Often this violence went beyond simple threats — during the 1934 textile strikes, police set up machine guns on the top of buildings downtown, while women and men in the streets below hurled stones at nearby police.

Though such violence should perhaps not be celebrated during Women’s History Month, it’s important to recognize the contributions and participations of countless women in the movement. If we fall back on dated notions that women in the early 20th century worked solely in the home or lacked the organizational know-how or political acumen to organize a strike, we miss out on a major moment in labor history, as well as a crucial perspective on the issues faced by working class women.

More information about the labor movement can be found at the Rhode Island Historical Society’s Mary Elizabeth Robinson Research Center, including the sources cited for this post: “Rhode Island Women Activists in the 1934 General Textile Strike,” the honors thesis of Adena Meyers; “Red Flame Burning Bright: Communist Labor Organizer Ann Burlak,” an article by Quenby Olmstead Hughes in the Rhode Island History Journal, Vol. 67, No. 2; and ephemera from the Sayles Finishing Plant available in the manuscript collection.

The Robinson Research Center is open Wednesday through Friday, as well as the second Saturday of each month, from 10am to 5pm. Materials are stored in the closed stacks and will need to be paged by library staff. Materials are retrieved at 10:30am, 11:30am, 2pm, 3pm, and 4pm (books only).

The Rhode Island Historical Society also has a lesson plan available for free download here.

RIHS intern Rebecca Hansen is a senior studying English at Brown University.