While reading through a 1916 guide to the RIHS’ old Cabinet building, I came upon an item which piqued my curiosity: the seal of the Fruit Hill Detecting Society. According to a description, it is a large metal emblem emblazoned with the image of a horse. This item now resides in a storage area in the John Brown House, where it is yet to be inventoried. Since I could not search through the assorted boxes and shelves in-person, I decided to delve into the history of the Fruit Hill Detecting Society.

State and local law enforcement in the 18th and 19th-century New England was small, overworked, and ineffective at the prevention of crime. Employment in the constabulary was undesirable — chiefly because many officers were charged with the task of tax collection — and appointees frequently refused the position. As early as the 1780s, wealthy townspeople turned to private organizations to protect their persons and their property. In June of 1830, one such group established itself in the North Providence village of Fruit Hill. It would remain, until 1893, at the service of all dues-paying members.

The Fruit Hill Detecting Society’s territory was the Fruit Hill Tavern (formerly on the corner of Fruit Hill Avenue and Smith Street) and everything within a six-mile radius. The mission of the society was to apprehend horse and carriage thieves, and to return stolen horses. The larceny of horses was a chronic problem across the Northeast, and the impetus for the establishment of many similar specialized protective societies. According to the historian of the Brownsville (Pennsylvania) Horse Company, ‘the horse has long been a favorite object for larceny, not only for its intrinsic value, but as containing the essential element within itself of putting distance between the flying fugitive and his pursuers.’

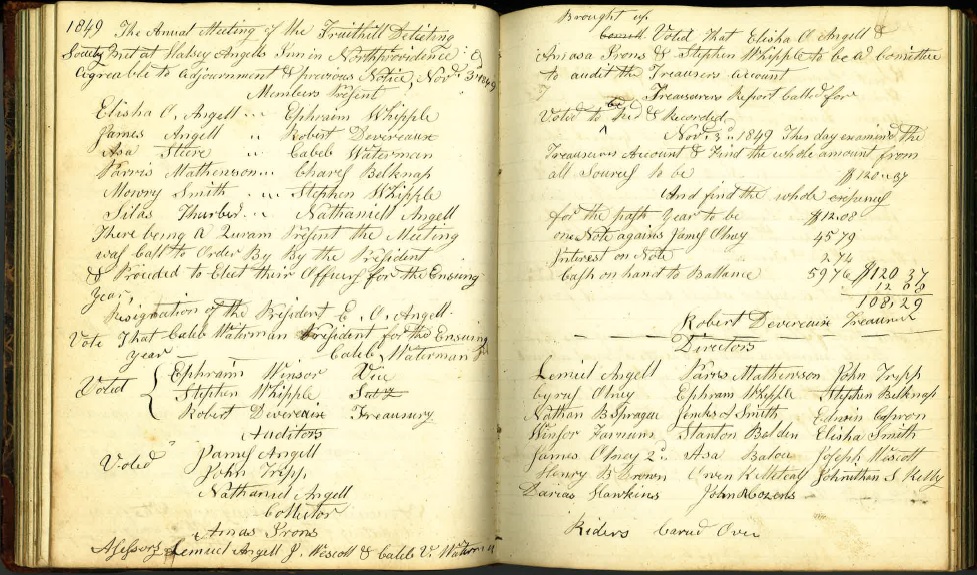

The society relied heavily on its many connections to locate stolen horses; earmarks and painful brands indicated each animal’s original ownership. The September 4th, 1890 edition of the Providence Journal has an interesting account of such a search and the bureaucratic processes which were entailed.

A special meeting of the directors of the Fruit Hill Detecting Society was held Tuesday evening to take action on the theft of Mr. Charles Fletcher’s team a week ago. The President had incurred considerable expense seeking to recover the stolen property. A number of pursuers were out trying to trace the stolen team, and the President desired the sanction of the directors to continue the efforts and necessary expense. The board fully endorsed all that had been done and directed that no cost or trouble be spared to recover the $700 turnout if possible.

When a thief was caught, the society would bring legal action against them — sometimes with an arrest warrant granted by the state. More often than not, however, missing horses were recovered after they had been abandoned or sold. The following is another excerpt from the same article.

Tuesday afternoon Mr. Beane and H. O. Martin recovered the horse stolen from the barn of Supt. Congdon at the Merino Mill village last week. The animal was found in East Providence. It followed a farmer several miles on the road between Tuanton and East Providence and had only a strap around its neck. No trace of the harness or phaeton buggy could be found, but search for them will be begun in the vicinity of Taunton.

Today, as Americans across the country reconsider the duties of the police force, it is prudent to turn back to the past in order to see what things have worked before. Though far from being an ideal model, for over sixty years, the Fruit Hill Detecting Society kept horse thieves at bay from its members.

Sources:

- Rhode Island Historical Society: Museum illustrating the history of the State. Providence, RI: Rhode Island Historical Society, 1916.

- Greene, Barbara and Thomas. Images of America: North Providence, Volume II. Charlestown, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 1997.

- Fruit Hill Detecting Society Meeting Minutes, MSS 432, Box 1, Folder 1, Rhode Island Historical Society.

- Fruit Hill Detecting Society Blank Warrants, MSS 432, Box 1, Folder 8, Rhode Island Historical Society.

- Szymanski, Ann-Marie. “Stop, Thief! Private Protective Societies in Nineteenth-Century New England.” The New England Quarterly 78, no. 3 (September 2005): 407-439.

- “Two stolen horses recovered and pursuit of Mr. Fletcher’s team continues.” The Providence Daily Journal, September 4, 1890.