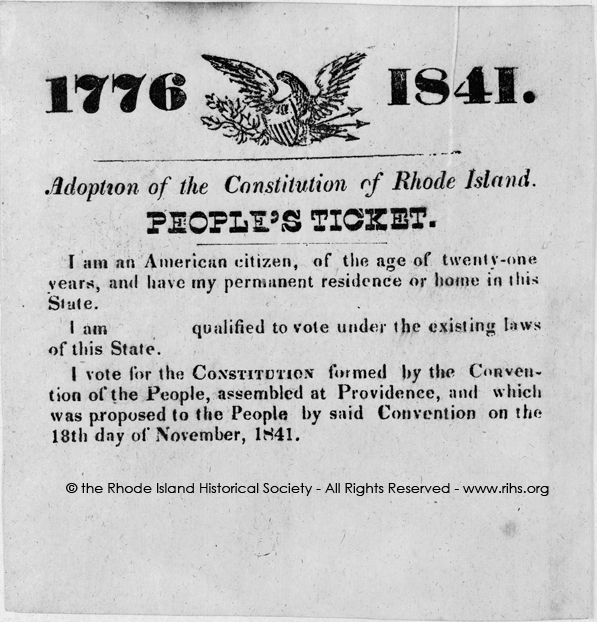

Protest against the property qualifications began as early as 1833, when Seth Luther protested the hoarding of political power in Rhode Island by “the mushroom lordlings, sprigs of nobility . . . small potato aristocrats” in his Address on the Right of Free Suffrage. By 1841, Thomas W. Dorr, son of wealthy China Trade merchant Sullivan Dorr, had joined the movement as the leader of the “Law and Order” Party with a platform of suffrage reform.

In preparing supporters for the parade, on April 15, 1841, New Age and Constitutional Advocate, (annual subscription, $1) assured readers that “No one need be afraid of adjournment on account of weather, as the snow is cleared off the ground on Jefferson Plain*, and active arrangements are going on for comfortable arrangements, let the weather be what it may.”

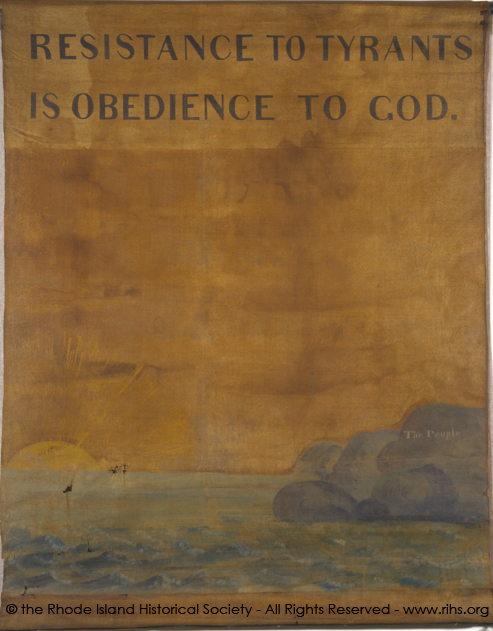

In preparing supporters for the parade, on April 15, 1841, New Age and Constitutional Advocate, (annual subscription, $1) assured readers that “No one need be afraid of adjournment on account of weather, as the snow is cleared off the ground on Jefferson Plain*, and active arrangements are going on for comfortable arrangements, let the weather be what it may.”Two days later, the procession set off from Benefit Street, led by the city’s Butchers in white frocks with blue sashes, riding two abreast on horses. In their center they carried a banner depicting an ox with the motto, “I die for Liberty.”

Not far behind them rode 22 Revolutionary Soldiers in five carriages. Among they carried a banner with the motto “We have fought for Freedom” on the front, and “Shall we die without our freedom” on the back.

The Suffrage Association had a strong sense not only of their rights, but of the history of the state, and of the nation. For Rhode Island, home of Roger Williams, to cling to a King’s charter was absurd tyranny–and after the procession, at a meeting of the Association where toasts were read, the second toast was to Roger Williams, “the bold and successful asserter of the rights of man–his monument is the gratitude of millions who have since been emancipated from the shackles of political and religious intolerance.”

We forget sometimes, in our hurry, that the men who fought in the Revolution did not make this country in a day, and they did not experience American democracy as we do. Men like Jeremiah Greenman set off at 17 to fight against a king: when they won, what were their rights, exactly? Without property, they couldn’t vote. How different was it to be Greenman living under a President instead of a King?

Dorr and the Suffrage Association and the Law and Order Party saw their movement as a revolution as much as that of 1776, and in many ways it was, threatening the established order and transferring power, by ballot, to more of the people. Instead of guns, they carried banners, several of which survive in the RIHS Museum Collection. What the Law and Order party and the Dorrites remind me of today is Occupy Providence.

~Kirsten Hammerstrom, Director of Collections

*Jefferson Plain, a high point overlooking the Cove Basin, is now the site of the State House.

I have nominated you for an inspiring blogger award

Thank you!