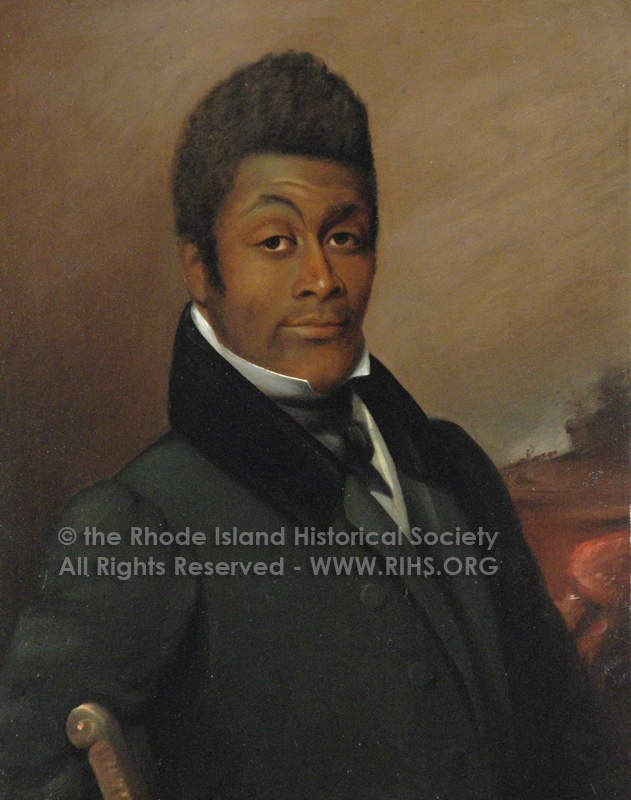

In this portrait by local stonecutter and artist John Blanchard, the sitter’s inner life rises to the surface. We don’t know exactly when the portrait was made, but it must have been made before Howland, along with his wife and daughter, emigrated to Liberia in 1857.

When Thomas Howland applied for his passport, the Providence Journal reported on the response he received, and the story was picked up by the New York Times, where it ran on October 23, 1857. Howland had applied through a Providence notary, Mr. Martin, who received the following reply: “Mr. Martin must certainly be aware that passports are not issued to persons of African extraction. Such persons are not deemed citizens of the United States.”

This response came in the wake of the Dred Scott decision of March 6, 1857. Howland’s expression is all the more resonant given that he was a citizen with voting rights in his home state of Rhode Island, and was elected warden of Providence’s Third Ward in 1857, the first African American elected official in the city. After Dred Scott, is it any wonder Howland left for Liberia?

The New York Times reported that he was leaving with his wife and daughter, who intended to “engage in teaching” in Liberia, a task for which she had qualified herself in Providence’s public schools. In 1857, the Blanchards left Providence for life in Africa, where he became a sugar manufacturer.

~ Kirsten Hammerstrom, Former Director of Collections (at RIHS 2000-2017)

Thanks Kirsten; is his portrait on public display?

He’s currently on display at the URI Feinstein Gallery (80 Washington St) but we will be picking him up on March 1. Later this spring, he will be featured in the Faith & Freedom exhibit to open at the John Brown House Museum. Look for him in coming weeks!

think you mean the HOWARDS left for Africa? or did the Blanchards go too?

Is he related to the Howland family from the Mayflower?

Very interesting part of history. Thanks for this post.

He was elected 1836 or 1839